Our Future

We need to create the future we want, which is different from avoiding what we fear.

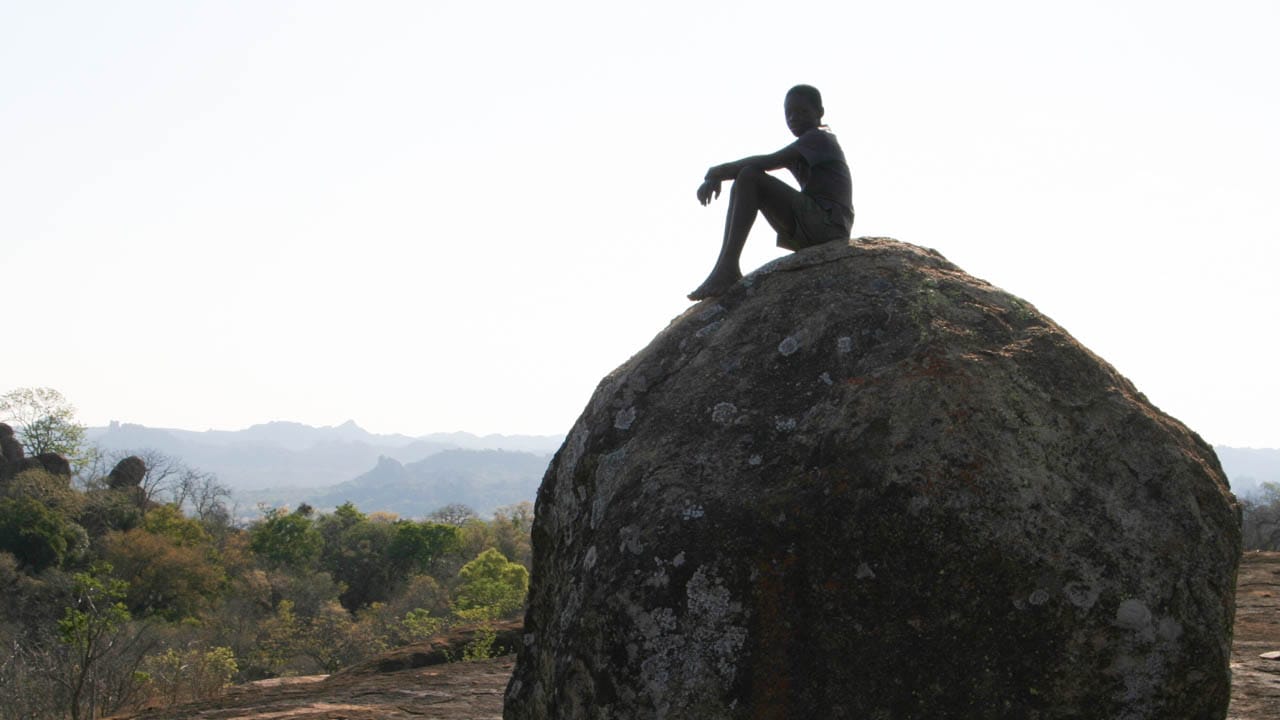

I want us to imagine our world in a few centuries time – and the best future we can picture, for humanity as a whole. This future will be rich and sustainable, and in balance with wider global ecosystems.

Imagination allows us to think in hopeful, creative and ambitious ways. I often focus on the year 2222. If humanity still exists after two centuries, it must have solved what now seem like impossible, existential problems. This tricks my brain out of feeling hopeless – giving me room to breathe, then explore fresh ideas.

To be practical, this exercise will not rely on futuristic technologies we can't build today. This thought experiment challenges us to look harder at real problems, rather than simply escape them with magical solutions.

Thinking so far ahead will help us recognise what is truly useful and meaningful, and what are temporary distractions. We can't predict specific details about the future, so choosing this lens forces us to focus on broader patterns, deeper causes and new solutions. Rather than a soap opera of weekly political crises, we'll examine the pressures driving social issues. It will shine new light on current challenges, and suggest fresh practical solutions.

The purpose of a thought-experiment ... is not to predict the future ... but to describe reality, the present world.

Ursula Le Guin

We need new conversations.

Business as usual is not working. The obvious short-term, local solutions often add to global problems. Politicians chase endless economic growth, but this undermines the environment we all rely on. We fear both population growth and population decline. Our societies force us to compete with one another, which fuels insecurity. We know we can't all be winners, but popular culture tells us success is all that matters.

Incremental improvements aren't enough alone, while partial solutions can make things worse. This is because we've outgrown paradigms we relied on, which creates interlocking crises. We need to develop new structures to support society. We need new visions to guide us to sustainable and inclusive solutions.

Our current reactive, firefighting perspective automatically moves from one crisis to the next. This only offers incremental trade-offs, or bad options. We become locked into evolving on pre-set paths, instead of actively making choices to shape our future.

Working backwards, starting from a future we actually want, helps break this pattern. Imagining our ideal future frees us to be ambitious and creative, and establishes the direction we want to move in.

We need a future which is hopeful, inclusive and decolonial.

We need a clear destination to aim for.

Together, let us reject the clamour of fear and listen to the whisperings of hope.

Statement on Peace

New Zealand Quakers, 1987

A Hopeful Future

In this troubled moment, imagining a future we want may seem a naive exercise. A comfortable, peaceful, sustainable future seems impossible when news cycles depict a depressing array of conflicts; films show dystopian crises, and so do our documentaries.

Trying to uncover our deepest hopes and values is painful when these are so far from our current reality. However, we are collectively powerful – powerful enough to nearly destroy our environment largely by accident. We need to claim and harness that power, to achieve what we want. As we'll see, we also need to contain and deliberately limit that power.

We need to be not merely hopeful, but ambitious. Small steps are not enough to address the global collective problems we face now. From climate change and ecological collapse, to corrosive inequality and radicalised politics, we need radically new collective solutions.

A hopeful vision will renew energy and a shared sense of direction, when many of us feel confused, isolated and frustrated.

An Inclusive Future

Like Rawls' Veil of Ignorance, a calmer future is one where everyone can live a good life. Societies where large groups only survive at the margins are not stable, or ideal.

Currently, 'rich' cities and countries, and the lives of the relatively fortunate within them, dominate political and economic priorities, and our collective imaginations. Megacities which built their infrastructure in periods of unusual wealth are historical outliers, so their norms and 'solutions' mislead us. Poor nations are expected to catch up by adopting a clearly broken development model.

Shifting the focus to including the excluded first creates a new perspective, and entirely new ways forward.

A Decolonial Future

Decolonising the future requires awareness of the cultural and historical baggage we all carry. European fears of Malthusian hunger and overpopulation now extend down into billionaire bunkers, and up into space. Fictitious histories feed empty nostalgia for golden ages, or fantasies of a limitless future amongst the stars.

We are products of a complex, violent, divisive and contested past. The resulting traumas limit our present realities. Unexamined, they also limit our imaginations. We adopt a defensive posture, bracing ourselves for continued scarcity and conflict. The dark shadows cast by historical exploitation and inequality makes it hard to see where we have already loosened the shackles of scarcity.

Recognising the deeper historical patterns encourages a more grounded historical perspective, and a more unified global narrative. It will show how urbanisation, industrialisation and infrastructure are at the heart of both past and current crises, and how we can move forward.

An integrated narrative about the past is essential to counter resurgent stories of racial, national and cultural superiority. We also need a better understanding of how economic activities can be sustainable, and in balance with the environment. (A focus on the worst historical exploitation can obscure this possibility.)

New thinking is challenging, but I have fresh insights to get us started. We'll see beyond current crises, grasp their roots, and find lasting solutions.

We need to change tracks in three areas:

- infrastructure - new transport to free us from megacities

- economics - reducing rat-race pressures for endless growth

- culture - challenging pervasive and toxic exceptionalism

Imagining a calmer future highlights the systems which support our survival, often invisibly. Currently too many people are born on the wrong side of the tracks – or far from any infrastructure at all.

Infrastructure embeds social priorities, values and options, then shapes societies over generations. 'Industrialised' economies rely on older systems, easily taken for granted until they start to fail, and need expensive renewal. However, most of the infrastructure humanity needs is not invisible – but has not yet been built. This presents challenges – and opportunities.

Our legacy infrastructure is creating key bottlenecks and market failures. These drive us to overcrowd megacities, which in turn inflate economic pressures. We will begin there: